Everything Americans Need to Know About Cricket

The other global game

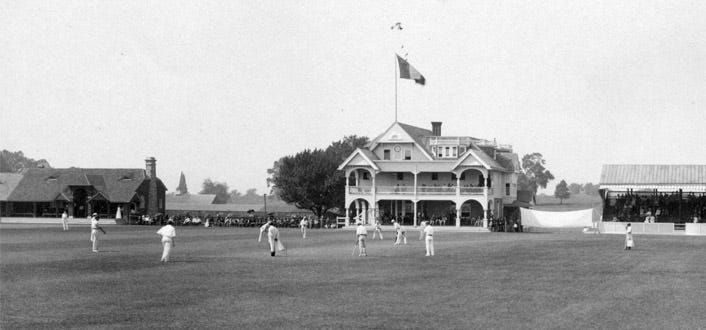

Once upon a time, in 1751, New Yorkers actually ventured to what is now the Fulton Fish Market to watch a cricket match between the New York XI and a visiting London XI. This was not an eccentric afternoon that everyone agreed to forget. Cricket was firmly embedded in New York life, to the extent that modern Manhattan has been constructed directly on top of several former cricket grounds, as if the city dealt with the situation by building over it and changing the subject.

Central Park once had its own cricket field, and, to this day, there’s a spot still called East Field, marked by a plaque announcing that it used to be a cricket ground. And in 1844, in New York, Canada beat the United States at cricket in what’s generally considered the first international sporting match of any kind, a fact that suggests America was playing global sport early on, before deciding it would rather invent baseball and never speak of this again.

Then the Civil War happened, and cricket rather lost momentum. Baseball, on the other hand, was simpler, faster, and came with the possibility of money, which tends to focus the mind. Quite a few cricketers sensibly switched codes, and baseball got very good at presenting itself as proudly, patriotically American.

Cricket didn’t vanish completely. It lingered in pockets, particularly around Philadelphia, where it became a pleasant country-club pursuit. But by the time the international cricket authorities finally let the United States into the club in the 1960s, the game had become a minority sport, largely played by expats on borrowed bits of parkland.

All of which explains why cricket now arrives in America feeling faintly exotic and oddly familiar all at once. The game has a history in the US. It’s just been waiting an extremely long time for anyone to remember it.

The cricketing universe, in all its baffling glory, is ruled by what the ICC (International Cricket Council) solemnly calls its Full Members, which sounds like a loyalty program offering bonus points on beige trousers. These include Australia, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies (yes, the whole Caribbean in one cheerful cluster), Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Ireland, and Zimbabwe.

Of course, there is also the unofficial hierarchy, the bit no one writes down but everyone knows, where Australia, India, and England strut about like they own the place, flicking imaginary lint from their lapels and pretending not to notice the others quietly seething behind them.

Which brings us to the cricket most Americans crash into by accident, usually while visiting England or Australia and just trying to order a sandwich. These two countries don’t like cricket; they take it personally. Utter one syllable of “Ashes,” and entire families start vibrating.

Australians puff up like cockatoos on caffeine.

English supporters look wounded yet determined, like men queueing for cheap suits at Marks & Spencer.

And before you know it, someone’s shouting about a match from 1882, someone else is Googling “Bodyline is what?” and you’re clutching a cheese toastie wondering if you should call for help.

Every two years, Australia and England engage in a sporting contest so ferociously polite that it involves standing around in white or cream-coloured trousers and battling over a tiny burnt piece of wood kept in a glass cabinet. This object is known as The Ashes, and it is housed at Lord’s—the grounds of the Marylebone Cricket Club in London, because England won it once in the 19th century and never saw a reason to let go.

This is cricket.

A Brief History

Cricket began in England, which explains nearly everything that followed. The Ashes urn exists because an English newspaper jokingly declared English cricket “dead” after losing to Australia in 1882. The Ashes were said to have been taken to Australia. Someone later produced an urn containing ashes of something (apparently a burnt bail), and the joke got out of hand.

It remains at Lord’s because England prefers the concept of ownership to the inconvenience of winning it back.

What the Cricketers Wear

Test cricketers dress like Edwardian bank clerks on a seaside holiday, striding to the sand in white. In the shorter formats, they wear aggressively coloured uniforms that resemble pajamas designed by a marketing department with access to energy drinks. Helmets are worn, but only while batting or if fielding at silly point. This is considered sufficient.

The People Standing Around

At any given time:

Two batters are “in.”

One bowler bowls (not throws) the ball from one end.

Another bowler waits politely at the other end for his turn which occurs after six balls.

Ten fielders arrange themselves in positions such as silly point, silly mid-off, silly mid-on, and cow corner.

These are real names. No one is joking. No one explains them.

How the Game Begins

Before a single ball is bowled, the captains walk to the middle of the field and toss a coin. This is how a sport worth billions of dollars decides who gets first use of the bat. Wimbledon does much the same, which is rather deranged. There are decades of training, millions watching, strawberries at mortgage prices, and the whole thing begins with two people solemnly shouting “heads!” like they’re choosing pizza toppings.

But back to cricket, where after winning the toss, the captain may choose to bat or bowl, a decision informed by weather conditions, pitch behavior, barometric pressure, personal intuition, and whether he himself is a batter or a bowler, as usually he chooses his speciality to be on show first.

This coin is:

Physical

Metallic

Entirely analogue

Once the toss is complete, everyone pretends this is a rational way to start a contest that may last five days.

The Aim of the Game

One team attempts to score runs by hitting a ball and running between two lines.

The other team attempts to stop this by hitting a small wooden structure behind the batter, called the wicket, which consists of three stumps topped by two bails.

Everyone agrees this is thrilling.

Strategy

Cricket strategy involves patience, attrition, psychological erosion, and waiting for someone to make a very small mistake four hours from now. It is chess, if chess lasted five days and occasionally stopped for sandwiches.

How Long It Takes

Test cricket lasts up to five days.

One Day Internationals last about eight hours.

T20 lasts roughly the length of a rational person’s attention span which is just 20 overs or 120 balls each if no one does anything silly.

All formats insist they are the “purest” form of the game.

Types of Players

Batters hit the ball.

Bowlers throw the ball in a way that looks illegal but isn’t.

All-rounders do both and are therefore resented.

Drinks, Tea, and Lunch (The Most Important Part)

Cricket stops regularly for drinks. It also stops for lunch. And for tea. At Lord’s, lunch may include roast beef, salmon, strawberries, and wine, which explains why no one is in a hurry.

This is not a joke. Play halts so everyone can eat.

Cricket vs. Baseball

Similarities:

Bat

Ball

Standing around

Differences:

Cricket bat is flat

Cricket ball is harder

Cricket players are encouraged to applaud good behavior

The game may end in a draw, which Americans may find spiritually upsetting

Etiquette and Bad Behavior

In cricket, it is considered polite to “walk” (as in walk off the field and let someone else have a go) if you know you’re out.

It is also considered normal to verbally dismantle your opponent’s self-esteem in something called sledging. These two ideas coexist peacefully.

Umpires (And the Third One)

There are two umpires on the field who make decisions.

There is also a third umpire, who watches television replays in slow motion and consults technology, geometry, and fate before confirming that no one is entirely sure what just happened.

An explanation of the “Rules of Cricket” as reproduced on tea towels and posters—writer unknown:

The Rules of Cricket

You have two sides, one out in the field and one in.

Each man that’s in the side that’s in goes out, and when he’s out he comes in and the next man goes in until he’s out.

When they are all out, the side that’s out comes in and the side that’s been in goes out and tries to get those coming in, out.

Sometimes you get men still in and not out.

When a man goes out to go in, the men who are out try to get him out, and when he is out he goes in and the next man in goes out and goes in.

There are two men called umpires who stay out all the time and they decide when the men who are in are out.

When both sides have been in and all the men have got out, and both sides have been out twice after all the men have been in, including those who are not out, that is the end of the game!

And that’s cricket: baffling, earnest, overfed, and deeply loved by people who promise it all makes sense eventually.

Nicole James is an award-winning writer of fiction and non-fiction, with a career that reads like the contents of a very glamorous, slightly chaotic handbag, filled with glossy magazines, boarding passes, and just a hint of ink-stained panic.

She’s spent years writing columns for a variety of newspapers and magazines. These days, she appears in The Epoch Times and Quadrant, when not buried under a mountain of PhD papers, valiantly attempting to complete a doctorate in Creative Writing while her cat judges her from the printer.